An Introduction to: The Nereid Monument

Introduction

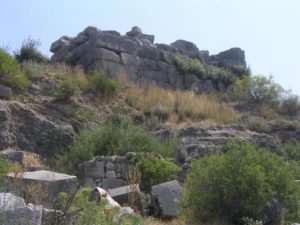

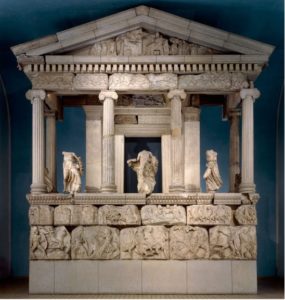

In 1848, antiquarian Charles Fellows began directing an excavation on the south-west coast of Turkey. Inspired by ancient literary descriptions of the socio-political influence of Lycia during the Persian Wars, Fellows began searching for material remains of the key Lycian settlement, Xanthos.[1] During the excavation, large stone fragments surrounded by the rubble of carved stones were discovered, just outside the city. These fragments belonged to the large platform-base of a monumental building, still standing in-situ and encircled by the debris of the buildings walls and decorative friezes, ruined during the fourth century CE.[2] These find were recorded by Fellow’s staff in detailed site journals which included colleague George Scharf’s sketches of decorative elements, architectural measurements and notes of the monuments contextual location. Like many British discoveries of the era, the finds were taken from their original site to the British Museum for study, the ethics of which are still debated today.[3] The ruins were partially reconstructed by a team led by Fellows including archaeologists, architects and specialist historians and the building was named the Nereid Monument, after the female nymph-like statues which were found within the same ruins. Three of these statues can still be seen today in the 1960s installation of the Monument’s eastern facade which remains in Room 17 of the British Museum (Figure 1).

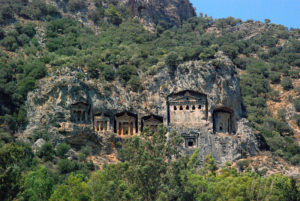

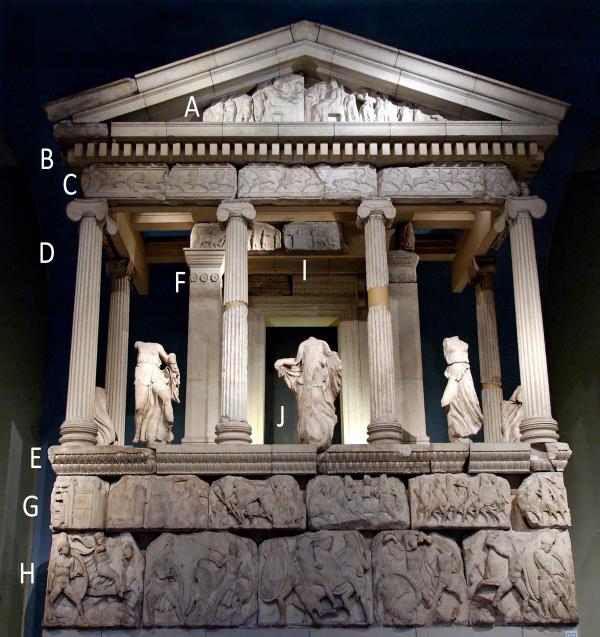

Figure 1: The original location of the Nereid Monument (left) and the reconstructed eastern facade in the British Museum.

Context

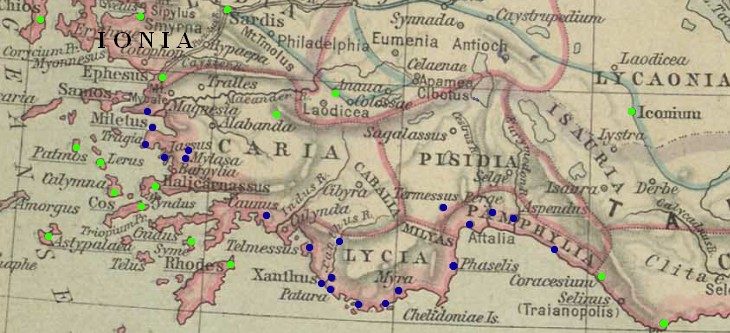

The Nereid Monument was built between 390 – 380 BCE and is thought to have served as a tomb for King Arbinas, ruler of the Lycian city of Xanthos (Figure 2).[4] The region of Lycia existed as an ancient geopolitical territory within Anatolia (modern Turkey) from around 1250 BCE to the rise of the Byzantine Empire in 395 CE. Lycia was renowned for persistently maintaining an unlikely level autonomy during Persian territorial expansion, whilst simultaneously siding with first the Persians and later the Grecians during their wars for political and martial dominance between 499-449 BCE (Figure 3). Despite being built during the Achaemenid (or ‘First Persian’) Empire, the Nereid Monument shows a concerted effort to integrate a range of Lycian, Grecian and Persian styles in its architecture, creating a contemporarily unusual and politically potent monument.

Figure 2: A frieze on the Nereid monument thought to show King Arbinas (left) and a coin minted with his contemporary (albeit styled) portrait. Note the Persian cap and clothing and the Greek Goddess Athena on the reverse side of the coin.

Figure 3: Map showing the location of Lycia in the ancient world.

The design of ancient Mediterranean architecture, especially civic or funerary buildings, often reflected the ideology of the society from which it derived. The ebb and flow of Greek and Persian dominance between 400-323 BCE, in turn, had an impact on the material cultures of Anatolia. Through the shape, material and decorative elements of a building, demographics advertised mythologies, lore and artistic orders, leaving a culturally identifiable mark on the landscape. The potency of these cultural monuments saw the material goods of a society developing in tandem to eras of external political influence, specifically to promote allegiance to, or autonomy from, those who dominated the region. This acculturation of material expressionism can be seen clearly in the Nereid Monument which shows a deliberate synergy of Lycian, Persian and Grecian styles.

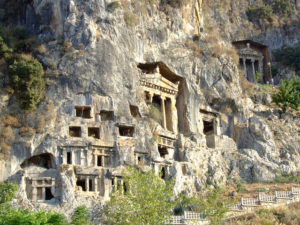

Traditionally, Lycian architecture infused with the surrounding natural landscape. Tombs and dwellings alike were cut into cliff faces and rock formations, creating settlements very similar to Persian tomb-complexes (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Lycian monuments cut into cliff rocks.

Although Lycian by birth and depicted in Persian attire on his tomb, King Arbinas was buried in a tomb that represented an Ionic-order Grecian temple. This monument is, in fact, one of the earliest examples of a Grecian-style temple-tombs discovered and it was made entirely from local Xanthian white marbles. The marble friezes which adorned the base, lintels, cella and pediments depict a mixture of Xanthian traditions, Persian clothing and Grecian soldiers. This combination of styles offers much rhetoric to the historian, provided it is reconstructed in the right order…

The Eastern Façade

Iconography in the ancient world was a multilingual method of expressing desirable characteristics and cultural ideologies. The folklore of a society produced symbols and allegorical attributes which could be reiterated across multiple media and act as reminders of the exemplary deeds of ancestors and immortals. Similarly, the sculptural detail on King Arbinas’ temple-tomb provides him with a posthumous legacy. A story of the King’s characteristics and qualities. At the top of the building sits a triangular gable (Figure 5-A), the pediment of which is decorated in bar relief to show Arbinas, his wife and children being attended to by servants. This scene is very similar to a well-recorded ancient portrayal of stability, hierarchy and dynasty on the eastern-side gable of the Parthenon. This Grecian parallel depicts the matriarch and patriarch of all the Greek deities, Hera and Zeus. It is unclear if this similarity is in competition or acknowledgement of the original scene but the same position, style and posturing are unlikely to be accidental.

In Greek architecture, the pediment decoration clarified to whom the temple was dedicated. Here, we see Arbinas’ ownership of the monument made quite clear by his position as the largest figure in the centre of the pediment. This use of a decorated (as opposed to the Lycian plain) pediment section, is a notably Grecian-Ionic trait.

Figure 5: The Eastern Facade (with notations).

Below the gable sits a plain marble cornice shaped with symmetrical dentils (Figure 5-B). This toothed style was popular in Lycian architecture and sits upon an architrave frieze made from three large monoliths (Figure 5-C). These three, decorated lintels sit atop four archetypal Ionic columns with volute tops, fluted monolithic shafts and double rimmed bases (Figure 5-D). This structural lintel-and-column technique is also Greek in origin and yet the frieze below depicts in relief, scenes of Arbinas performing traditional Xanthian activities such as hunting on horseback, feasting and offering sacrifice, all pastimes indicative of his royalty and courage[5]. The continuous nature of these images, lacks earlier Doric dividing trilopes, bolstering the argument of this being a very early Ionic temple-tomb. Whilst we currently see a four, tetrastyle row of columns on the eastern facade, this elevation originally made one short side of a four-sided, freestanding structure. Encompassed by a peristyle colonnade were sixteen columns in total; two tetrastyle faces at the east and west and two parallel hexastyle lengths facing the north and south.

The four columns of the eastern facade currently sit atop a deep stylobase, which in turn is topped with a border of slim capitals, each of the four adorned with double rows of egg and tongue moulded motifs (Figure 5E). On the corners of these motifs are palmettes- a symbol used by many ancient cultures to represent sun, life and fertility. Here we see a more subtle mixing of imagery with the palmettes engraved on the stylobase displaying Grecian traits, whilst the repeated form on the walls of the inner chamber are Lycian variants (Figure 5E & F). Below the slim-capital border sits a row of six larger, rectangular marble slabs. Carved in bar-relief these Xanthian marble friezes depict Lycian infantry warriors defending a besieged town, perhaps Xanthos itself (Figure 5G). Beneath these scenes of defence are a set of marble slabs, larger still, showing Greecian mounted cavalry and infantry warriors fighting oncoming barbarians in various attires (Figure 5H). Although it is not clear precisely who these attackers were, (or if there generic images of the Persian wars) the scenes suggest the defenders of the besieged Lycian town welcomed the Grecian support. It is not inconsequential that these images are large, detailed and positioned at eye-level to those passing by the inaccessible tomb. These parabolic displays served as a reminder of Xanthian history and make a bold statement. From the top to the bottom of the temple the story of Arbinas and thus, the Xanthians, develops from traditional regality, to Persian influence, external conflict and Grecian support, perhaps pertaining to Lycia’s eventual alliance with Athens after many years of supporting the Persian uprising.[6] The statement nonetheless is clear. This is King Arbinas. He had a Lycian dynasty, Persian power and Grecian allies. Here is a statement of a different kind of conquering king – The ability to remain independent whilst also getting the best of both quarrelling sides of a global war.

The high stature of the pediment is a dominantly Lycian feature and with no evidence for stairs ever being present, this tomb appears to have been designed as an elevated monument, rather than an active building. Access would have been difficult without ladders (and scaffolding?) and certainly not without the correct permissions.[7] Those who did see the inside would have confronted a single, central room or cella, within which the sarcophagus itself was interred. Alongside the coffin were two Greecian dining couches, supposedly for use by the King and his son in the after-world. Surrounding this central cella stand four pillars, contrastingly plain and square with those of the peristyle facades. These Lycian columns are also topped by an architrave frieze, this time showing Xanthian-clad citizens performing animal sacrifices and religious libations, such as those offered before a battle (Figure 5I). The overall theme of these scenes is one of traditional practice, reiterating that Arbinas was no stranger to the danger, bravery and piety required of a king and leader. It is perhaps not coincidental then, that the traditionally Lycian inner cella of a Xanthian tomb built during the First Persian Empire, is protected by a surround of Greecian-Ionic frontage.

The Statues

The Nereid Monument was adorned with many sculptures beyond the aforementioned friezes. Eleven female-figures, two poised lions and multiple fragments of cornerstone adornments or acroteria were found. The acroteria were carved with images of male and female figures and the mythological connection of these pieces is still unclear due to their fragmentary nature. The lions are sculpted in a pose common in the ancient world, growling with front legs outstretched with the rear and tail elevated. The eleven female statues have been identified as Nereids and it is from they that the monument derives its modern name. It has been reasonably argued that eliyãna is perhaps a more fitting term for these maidens, the eliyãna being Lycian water-nymphs of fresh-water springs, some of which were found to the south of Xanthos [8]. The original position of these statues on the monument itself is also contested. It is unclear, given the varying quality of preservation, whether these sculptures represent the same mythological beings in high quantity or different mythological persons. It is also highly likely (due to the odd number) that there are some sculptures missing. The women are, nonetheless, freestanding- sculpted in the round by high-relief masonry akin to the Greecian Classic-order famed for its hyper-realistic depiction of textiles (Figure 5J). The three statues currently displayed in the British Museum’s reconstruction show intricately detailed anatomical forms, veristic drapery and a variety of sea creatures carved around the feet of the figures.

Each of the Nereids appears to be dancing, dressed in peplos -a long garment typical of female-fashion in the Classic era of ancient Greece- with a diploidion (or belt) around the mid-drift. There are statue-settings between all of the columns, hence the suggestion that these figures danced around the whole monument. Whether Nereids or eliyana, the inclusion of a mythological form which could be recognised as both Grecian saltwater and Lycian springwater-nymphs, is contextually prudent. The city of Xanthos, where the monument was found, is located on the seacoast and at the mouth of the river Xanthus. These ports were key access points for Lycian trade, travel and territorial access and given the cultural synthesis of the entire Nereid Monument, it is likely that these sculptures were deliberately hybrid in nature to depict the common attributes between the river and sea and the cultures which were both connected and protected by them.

Conclusion

King Arbinas’ tomb was a rich monument built to commemorate the regality, heroism and dynasty of its inhabitant. As the king of a Lycian society which both influenced and was influenced by Persian and Greek cultures, Arbinas is portrayed as a keystone of power. Depicted in Persian dress, surrounded by Lycian allegory and protected by Greecian creatures, Arbinas’ legacy was visible to onlookers from all directions of approach. This tomb was carefully decorated, ensuring the complete acculturation of the artistic styles, fashions and architectural elements of the three most dominant territories of the age. The allegorical friezes’ multilingualism impresses a focused message of power, protection and progeny. The Nereid Monument is a fine example of how ancient art can tell the story of the conflict, coercion and collaboration of peoples past and indeed, of the historians who attempt to interpret them.

To explore the monument in 3D and for further information on the connection between Arbinas and Herakles, how this monument set potential benchmarks for the Telephos Freize at Pergamon and debates over the reconstruction of the tomb, see the below resources and bibliography.

Footnotes

[1] Herodotus, Homer

[2] Jenkins, I. 2006. Greek architecture and its sculpture: 8-10. Harvard University Press.

[3] St Clair, W. 1967. Lord Elgin and the Marbles. Oxford University Press.

[4] Siapkas, J. & Sjögren, L. 2013. Displaying the Ideals of Antiquity: The Petrified Gaze. Routledge, New York.

[5] Hornblower, S. 2011.The Greek World: 479 BC-323 BC. Abingdon: Routledge. P78.

[6] Hornblower, 2011. P76-79.

[7] Jenkins, 2006. P198-199.

[8] Robinson, T. 1999. Erbinna, the ‘Nereid Monument’ and Xanthus in Ancient Greeks West and East: 361-377 & Thurstan, R. 1995. The Nereid Monument at Xanthos or the Eliyãna at Arñna? In: Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Volume: 14, Issue 3. P355–359.

Bibliography

Ancient Sources

Herodotus, Histories. (Loeb Edition)

——————

Ebbinghaus, S., Tsetskhladze, G.R. (ed.), Prag, A.J.N.W (ed.) & Snodgrass, A.M (ed.), 2000. A banquet in Xanthos: Seven Rhyta on the Northern Cella Frieze of the “Nereid” Monument. London: Thames & Hudson.

Hornblower, S. 2011.The Greek World: 479 BC-323 BC. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jenkins, I. 2006. Greek Architecture and its Sculpture. London: British Museum Press

Pryce, F.N & Smith, A.H, 1892. Catalogue of Greek Sculpture in the British Museum, Volume I-III. London: British Museum Press.

Robinson, T. 1999. Erbinna, the ‘Nereid Monument’ and Xanthus in Ancient Greeks West and East: 361-377.

Siapkas, J. & Sjögren, L. 2013. Displaying the Ideals of Antiquity: The Petrified Gaze. Routledge, New York.

St Clair, W. 1967. Lord Elgin and the Marbles. Oxford University Press.

Sturgeon, M.C. 2000. From Pergamon to Hierapolis: From Theatrical Altar to Religious Theater in: Thomson, N., Ridgway, B.S (eds.) From Pergamon to Sperlonga: Sculpture and Context. University of California Press.

Thurstan, R. 1995. The Nereid Monument at Xanthos or the Eliyãna at Arñna? In: Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Volume: 14, Issue 3, P355–359.

Further Resources

Photogrammetry 3D view of the Nereid Monument can be seen here on the Archaeology Grrl YouTube Channel.

Photo Credits:

Figure 1- Jona Lendering. The British Museum.

Figure 2 – Jona Lendering. The Classical Numismatic Group.

Figure 3 – William R. Shepard.

Figure 4 – WikiVoyage_Simm. Allen Watkin, London.

Figure 5 – Bunny Waring.