21st Century Classics – Why Bother?

If there is one thing Lockdown number 5,409 has taught the collective ‘us’, it’s adaptation. With enforced periods of dull, gray nothingness, Covid has presented many of us with time to think, reflect and redirect our unspent energies. As an experienced archaeologist and a relatively green Classicist, I find myself confronted more and more with questions such as

Why is classics important?

What has classics ever done for us?

How is classics applicable to the modern world?

As a teacher, I want to confront this head-on. As a researcher, I am fretful about the answers. These questions largely arise from the recent intensification of movements for justice. These (rightful) demands for equality in treatment, education and opportunity clash with leading conservative governments, whose elitist motivations severely reduce choice in working-class schools. The subsequent conformity of institutions who (either through coercion or enthusiasm) are systematically deleting Humanities programs in favour of increased Science-based modules, fail to see the ‘profit’ in studies of ancient history.

The truth? Elements of Classics are outdated. But we’d be much worse off without the discipline as a whole. To understand why we should bother with Classics (and indeed many history-based subjects) we first need to break down what ‘Classics’ really is and why it matters.

What is Classics?

So let us start at the beginning. What people think Classics is:

- Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity, and in the Western world traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature in their original languages of Ancient Greek and Latin, respectively. – Public, Wikipedia, 2021.

- Classical Studies is a branch of the humanities that is primarily concerned with the ancient civilizations of the Greeks and the Romans, as well as many contemporary Mediterranean cultures, and particularly the extensive body of literature and archaeological remains that these cultures passed on to us. – Academia, Oxford Classical Reference, 2021.

- Classical Studies is a study of the ancient civilisations of Greece and Rome without

involving the study of the Greek language or the Latin language. It encompasses historical,

cultural, religious, moral, literary and aesthetic elements, and it may touch upon the

scientific/technological area. – Administration, Scottish Qualifications Authority, 2021.

Already we can see themes and conflicts. In reality, Classics is all of these things and much more. It is the study of ancient written material of all genres, from all ancient civilisations. This includes satires, historiography, plays and poetry. Studies can be drawn from a broad range of evidence both in and beyond literary works, including graffiti, funerary inscriptions, papyri or coins.

Although Classics is often sold as the study of Latin, Greek and the Western world, in practice, the specialisms within this discipline are vast. One can study broad themes or niche topics from ancient clothing and concepts of gender -identity, to burial practices and political disputes. Ancient philosophies, the development of language, acculturation and economics can all be traced, cross-examined and tracked through time and this, naturally, stretches beyond modern Europe. Individual experiences of war or childbirth can be meticulously studied to gain a better understanding of community identities, what it meant to be ‘a Barbarian’. Classical studies allow the pursuit of these trends over time, tracking their influence on cultures, classes, genders and ages. The flexibility of the subject and its dectective-style piecing together of complex evidence, frameworks and contexts often creates unique departmental communities. Like archaeologists, classicists often claim they feel accepted within the discipline in a way that seems unlikely in other careers.

Classics is then, in short, a vastly multicultural and multilingual subject. But if the subject is so relevant to modern life, why is it dwindling in lower and higher education? The answer is simple. Classics has remained unchecked as a luxury-subject for centuries. Similar to other humanities and arts subjects, Classics is governmentally, industrially and publically fobbed off as being inapplicable and out of touch. Further government-imposed characitures of what Classics represents, ensures departments fail to receive the same funds, recognition and support as more respected areas of sciences and maths. Whilst the latter no doubt have their own value, the pitching of humanities vs science subjects benefits neither staff nor students on either side. Whilst Classicists may not have control over university restructuring, business plans and redundancies, to survive the discipline must address and react to that which it can control – a long-overdue reassessment of the way it is portrayed and (in some elements) performed.

Why is Classics Important?

After centuries of being a middle-class, white, and male-dominated pursuit, ancient history has for a long time, been the studies of the ancient rich and privileged, by the rich and privileged. The association of past cultures (notably ‘whiter’ Roman and Greek cultures) with colonial power, has provided modern authors with proxies in their political discourses. This has a self-sabotaging effect. Decontextualised elements of history – be they people(s), objects, symbols, behaviours or places – become embedded in modern narratives, simultaneously losing appeal to those who reject their modern implications and empowering those who have decontextualised them. Take, for example, Roman imagery and emblems used throughout Europe’s war-torn year twentieth century. Columns, eagles and wreaths which provided the Romans with allegorical attributes and cultural statements, began to appear in everything from bank architecture to nazi flags. It is not just the archaeological evidence that is affected – the words Republic, Democracy, Senate and Dictator are so potent in today’s society they are far-removed from meanings in the past.

This is, of course, nothing new. The Romans borrowed from the Greeks who borrowed from the Egyptians, who borrowed from the Mesopotamians. It is, however, the multifarious nature of attacks on cultural-heritage in the twenty-first century that threatens the past in new ways. The destruction of cultural memory during war now includes dynamite, the elitism in education now ties into managerial paychecks and the prescriptive nature of the curriculum (especially in the UK) adds to the potent ties between classicism and colonial-pursuits. Despite these hindrances, Classics still has the ability to recontextualise ancient knowledge and protecting our (global) understanding of the past. By addressing the critical and long-overdue development of the discipline’s fundamental values and motives, Classics as a community can circumnavigate these problematic (and still bolstered) preconceptions, making classics more accessible in the digital age.

21st Century Classics

This has, thankfully, already begun. There are many within the disciplines of archaeology, museum studies and classics who are pioneering the subjects towards new, much needed and more equally beneficial directions.

- There are free online MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) such as Prof. Matthew Nicholls’ Virtual Rome which brings humanities into the digital era, offering enrollees the chance to explore ancient Rome at their own pace through videos, essays, 3D models, virtual tours and exploratory digital maps. This course draws in participants from all abilities, backgrounds and geographies, providing a platform for unusual dialogues.

- There are charities that specialise in providing funds and opportunities to underrepresented groups, such as The Sportula and Classics Everywhere.

- There is a push in decolonising the curriculum to make Classics more accessible to all and to recontextualise the past – SBA and Rogue Classicist.

- There are networks simultaneously bringing together different disciplines and demographics such as SAHID NETWORK and Classics For All.

- There are diverse teams working on projects which address the importance of studying the non-elites of the past such as MAPPOLA.

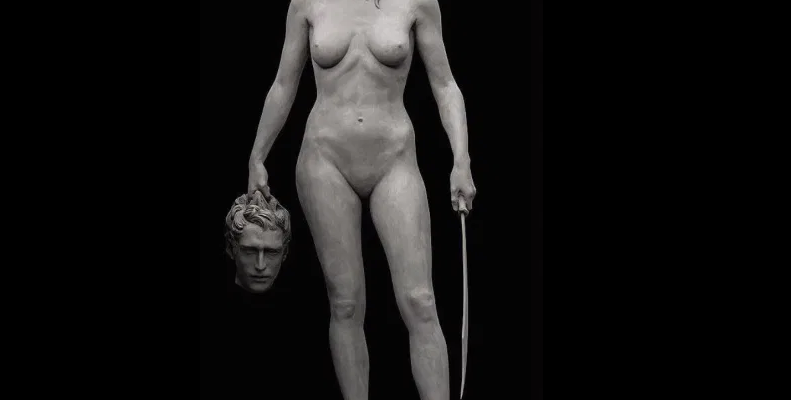

- Re-evaluations of long-held preconceptions are being challenged through new approaches to traditional subjects through artistic and interdisciplinary research such as the Medusa statue by Luciano Garbati, a 45-year-old Argentine-Italian artist based in Buenos Aires (pictured at the start of this article) which re-imagines the infamous Medusa/Perseus myth.

All these efforts, and more, bring diverse opportunities to those interested in studying and teaching Classics in the 21st Century. To move forward, we need to approach the subject from this entirely new perspective – one that confronts the prejudices of the modern era, which having been left unchallenged, continue to suppress the underprivileged and ultimately, destroys multiculturalism in the present and ancient worlds.

A Final Word

Image 1 – The re-imagined Medusa myth is a sculpture by Luciano Garbati, a 45-year-old Argentine-Italian artist based in Buenos Aires. The statue usually shows Perseus holding Medusa’s head.

Image 2 – On the left a marble frieze from the Roman Emporer Trajan’s Forum with an Eagle and a wreath – important images in Roman culture and mythology. Dating from the Second Century CE. On the right, a coin issued during the Third Reich Rule in Germany in the 1940s showing similar use of iconography.

Image 3 – 5 equally spaced, arms of different skin tones with closed fists raised in the air. The closed fist held high is a symbol of the BLM movement and represents freedom from the shackles of slavery.

Video by The Society for Roman Studies