Introduction To...

An Introduction to: Ides of March – Frivolity, Feasting and Folklore.

The Ides of March 44 BCE is remembered each year by history enthusiasts as the day of Julius Caesar’s assassination. The execution of the most prevalent Roman leader of his time by the co-governing senate was no small matter and is often marked as a turning point in Roman politics. Before this infamous day, however, the 15th March was already an important moment in the Roman calendar. As a time of religious celebrations and a deadline for settling personal and political debts, the ides of March marked a moment to reflect upon the death, renewal and celebrations at the end of an old year and the beginning of the next.

The Roman calendar(s) did not count days in the way modern calendars do. Days were referred to in hindsight with each date relating to three fixed points of a month –

- Nones (the nine days before the Ides of the month)

- Ides (the middle of the month)

- Kalends (1st day of the following month)

So the ides of March and what we call Septemeber would have been the 15th and 13th respectively. These periods were based on the lunar cycle (as opposed to modern sunlight based clocks) and in the earliest Roman calendars, the ides of March fell on the first full moon of the new year. Although moon cycles shift over the centuries, this date continued to gather more potency during the development of the Roman Empire, marking a fixed time in the year for important celebrations. Firstly, the ides in the Republican era was a sacred day dedicated to the Romans’ leading deity Jupiter. Late Republican and early imperial periods see an increase of events with a variety of feasts, dances and further festivals devoted to a plethora of deities from the goddess Perenna to the trees of Attis. By the late Imperial era, the ides of March was a time to recall and celebrate death of the old and the birth of the new, specifically, the changing of the old year to a new one.

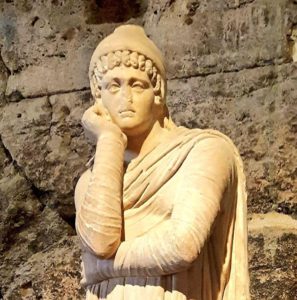

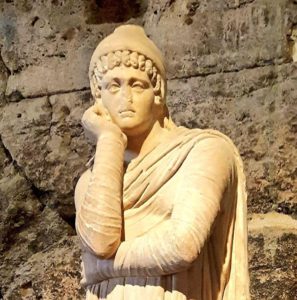

Whilst the appreciation of Rome’s leading god, and the goddess of the new year may seem obvious choices for ides celebrations, the story of Attis is a little less known. Attis’ story begins with him being a newborn child abandoned in a reed basket and found floating on the river by either shepherds or the great mother goddess Cybele (sound familiar…?). Attis grew up to be the consort of the aforementioned Magna Mater Cybele and from the first century CE Attis’ story was reenacted over the course of a of celebrations which straddled the old and new years. Beginning on the ides of March, the week which followed was full of festivities focused on mourning and celebration retold through the allegories and attributes of Attis’ mythology. The ides ritual involved the bearing of reeds and a procession that reenacted baby Attis’ discovery in the river. This was followed on the 22nd by the commemoration of his eventual death under a pine tree, during which a sacred pine was decorated in his honour and with an image of him hung on top (again, familiar?). Ths tree was then cut down and laid to rest on the 23rd at the temple of Magna Mater.

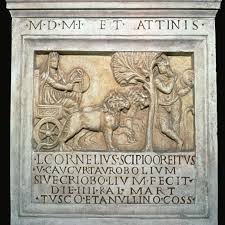

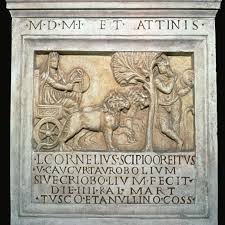

Roman calendar inscribed in marble. Credit: Sethanne Howard.

Self-flagellation, mourning and laying the tree (body of Attis) to rest in his tomb occurred on the 24th, before Attis rose again in rebirth on the 25th (and again). The 26th was a day of rest before the rolling of the sacrificial stone from the temple of the great mother to the river to cleanse it on the 27th (…). By the 28th there was much rejoicing for the reunion of Cybele the great mother and her consort Attis.

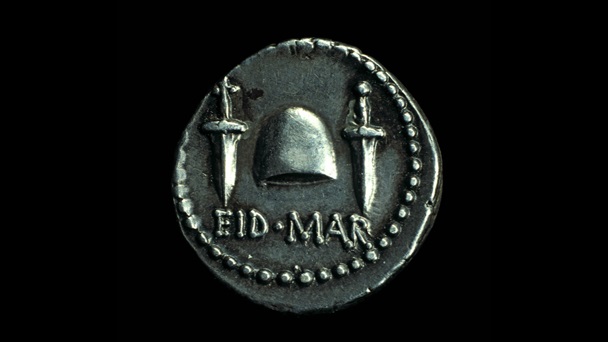

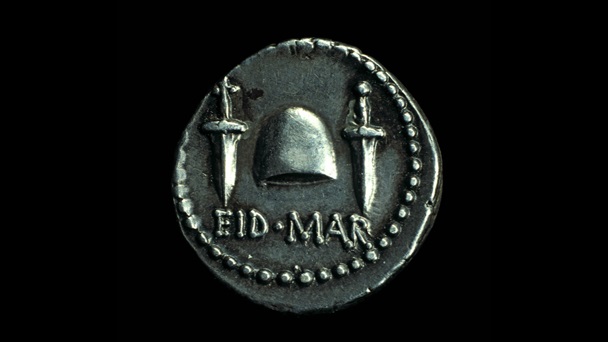

This story is incredibly similar to modern Christian celebrations surrounding Moses and the birth, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. From the decorated pine trees to the holy mother and the rolling of the stone, this Roman week, like Christmas, was also celebrated around the time of the new calendar year. The theme of frivolity, feasting and folklore can be seen throughout the holiday and reminds us of the importance and complete embedment of ritual and symbolism in daily Roman life. [Note particularly the use of Attis’ symbolic Phrygian cap on the reverse side of Brutus’ coin claiming himself the saviour of the Roman people from Caesar’s tyranny.]

So when we remember that execution in 44 BCE, let us not forget the context of this date throughout Roman history. For better or for worse, this calendar day always revolved around balance, debt repayment, celebration, death and new beginnings, making strong socio-political statements long before and after the potency of Julius Caesar and the other big JC.

[Attis portrait circa 2nd century CE from Hierapolis Agora at the Hierapolis Museum]

Title Image: [Brutus’ commissioned coin to celebrate the assassination of Julius Caesar. 44 CE. British Museum.]

Thank you! That was a fascinating and really informative blog post! I had no idea it was such a day of importance to the Romans