Heritage in Times of Conflict – A Reflection on the Culture Academic Forum 2018.

The following post was written but not fully published online in 2018. Enjoy!

On 18th April I was invited to attend the Heritage and Culture Academic Forum 2018. The topic of focus was: Heritage in Times of Conflict and included talks, a film viewing and discussion with a panel of specialists.

Chaired by Professor Roger Matthews an expert in Near Eastern Archaeology and the president of RASHID International (Research, Assessment and Safeguarding the Heritage of Iraq in Danger), the panel included:

- Tim Slade: Writer, Director and Producer of the film ‘The Destruction of Memory’ for Vast Productions, USA.

- Dr Lisa Purse: Head of Department and Associate Professor in Film, Theatre and Television, University of Reading.

- Professor Rosa Freedman: Professor of Law Conflict and Global Development, University of Reading

- Dr Dina Rezk: Lecturer in Middle Eastern History (19th / 20th Century), University of Reading.

/GettyImages-639630840-f5eaac1e4d964237bc70991061ff73eb.jpg) The event was both sobering and positive, introducing to its audience the tactical targetting and destruction of monuments and archaeological sites, by militant groups vying for power. The key argument was that the removal and/or protection of revered historic places during wars and political changes needs to be contextualised within the wider tragedy of human loss and societal reform. To prevent the belittlement of genocidal atrocities during conflict in South West Asia, the decimation of historic sites, museums and art is often overshadowed in reports. Local historians and cultural officials in affected areas of Iraq, Syria and Libya, however, say this problematically masks a critical element of Daesh’s programme of cultural oppression.

The event was both sobering and positive, introducing to its audience the tactical targetting and destruction of monuments and archaeological sites, by militant groups vying for power. The key argument was that the removal and/or protection of revered historic places during wars and political changes needs to be contextualised within the wider tragedy of human loss and societal reform. To prevent the belittlement of genocidal atrocities during conflict in South West Asia, the decimation of historic sites, museums and art is often overshadowed in reports. Local historians and cultural officials in affected areas of Iraq, Syria and Libya, however, say this problematically masks a critical element of Daesh’s programme of cultural oppression.

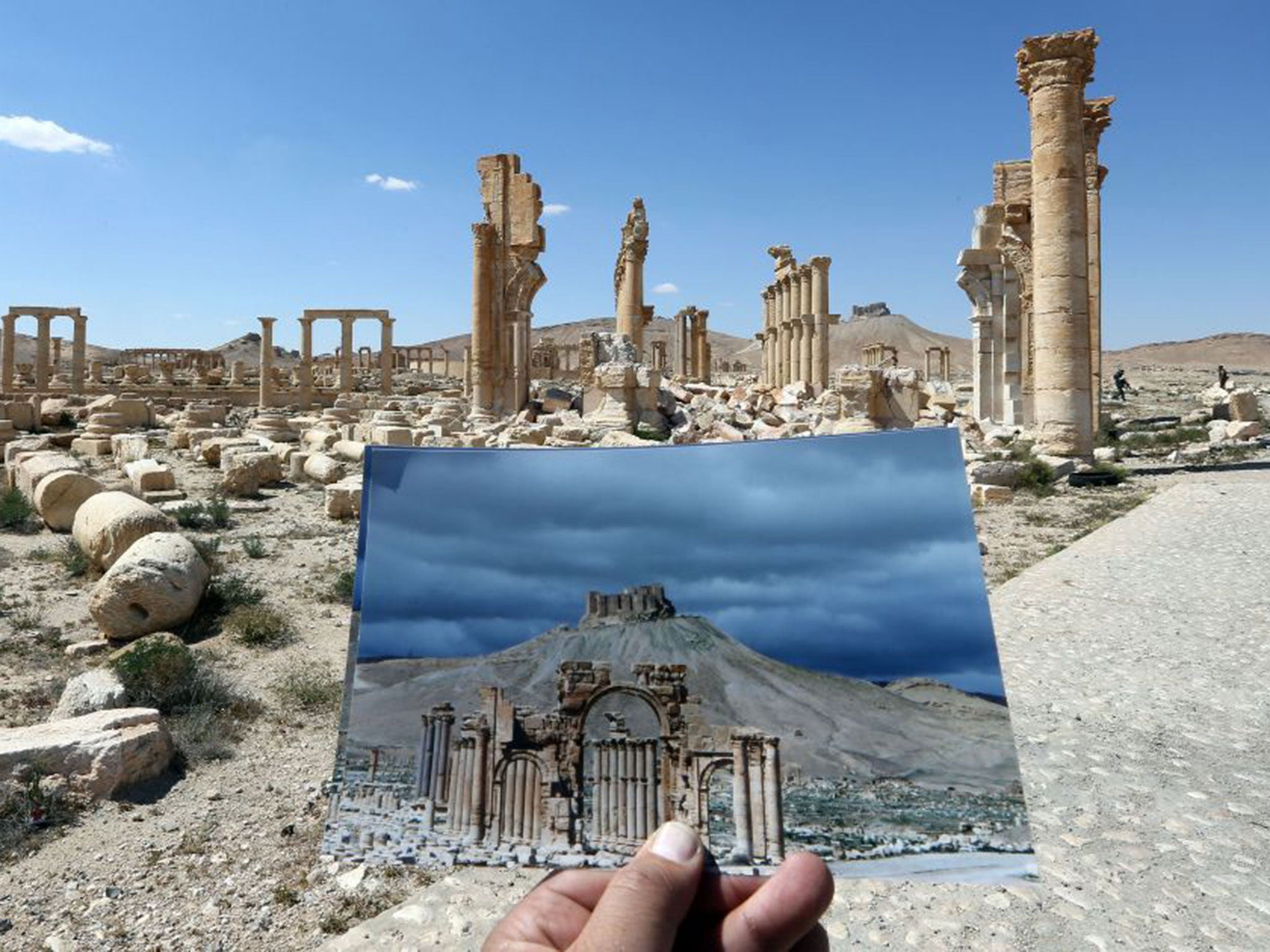

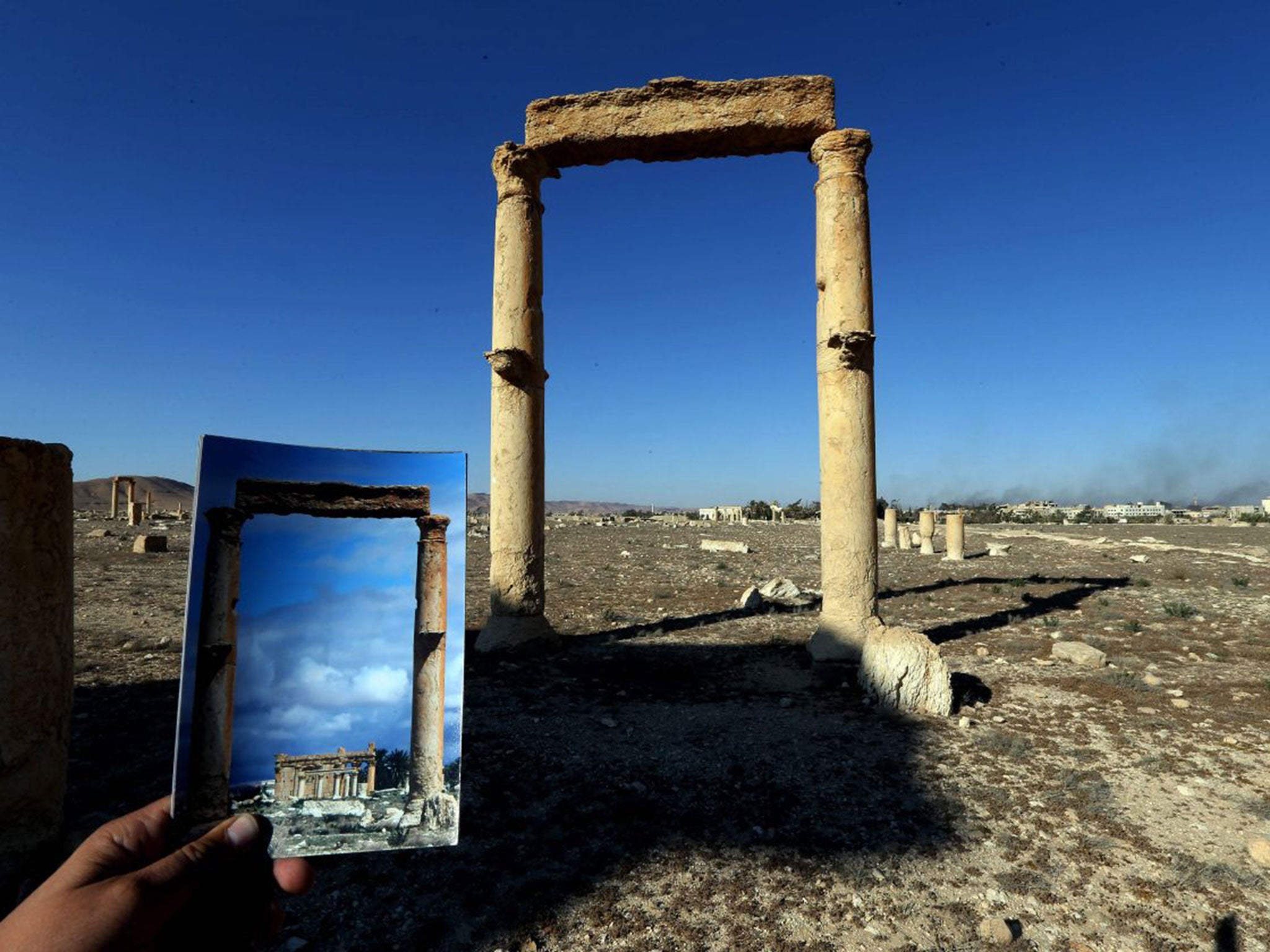

The destruction of ancient sites across the Levant has been gaining momentum in the last four years with sites of Roman and Greek origin being especially targetted by militant groups opposed to Western culture. These ancient societies have pluripotent associations with modern European society and Roman legacy is still visible in the architecture of its capital cities, the systems of law and education and even in the written and spoken language. There isn’t time today to discuss the complexities of this connection and how colonial aspirations of power have contorted the evidence of what Roman life was actually like, but as beacons of the perceived opposition, active group Daesh have been deliberately targetting archaeological sites which display Roman features.

Having stood for over two thousand years, it is important to acknowledge that these sites are not just symbols of Daesh’s opponents, nor Imperial power. Long-standing monuments create a sense of awe, inspiration and identity for those who still use them today. First-hand accounts of the devastating impact losing these monuments has had on communities, research, facilities and economies are widespread. Tall columns, ruins and caverns offer more than iconography and have provided inspiration for storytelling, architecture and tourism. They act as venues for gatherings, celebrations, festivals and of course, provide evidence for research and conservation. The multifaceted connection between neighbouring communities and ancient ruins has been noted as much as their supposed advertisement of westernisation by those groups who seek to destroy the sites. More recently, the local historians, tour guides, guardians and researchers who refused to abandon the archaeology, also lost their lives.

(All photographs in of Palmyra accredited to and owned by: Joseph Eid)

So why is this prioritised by Daesh and other militant groups? The videos of Palmyra columns being reduced to dust packs an emotive punch, even more so when coupled with the realisation that all the local caretakers, lecturers, farmers and curators were murdered alongside it. At their own admission, Daesh has praised the loss of Roman monuments, saying it prevents future education of a perceived westernised nature and dramatically displays the level of commitment the destroyers have to their cause. The questions open to the panel were thus: What can be done to save the people, knowledge and archaeology of heritage sites? What communication gaps are there between communities? How do we unify more cohesively to respect and help protect the knowledge and cultural reciprocity these places offer communities?

The answer, it seems, lies largely in education. Not just at universities, but between all groups involved in conservation and preservation. The unifying connection between local, global and cultural identities should not be underestimated in this instance and the focus should not be on who has the correct interpretation of these sites, but how we can preserve them for everyone’s interpretations. Groups such as Daesh already comprehend the impact the destruction of these sites has on a local and global scale with some videos showing the destruction of UNESCO sites, having been proven to be orchestrated. Real-time lidar and aerial photography shows instead, the looting and selling of antiquities to fund militias groups. This makes a stark statement about how more shocking to the world is the destruction of ancient monuments as opposed to the selling of ancient artefacts, but this is a blog for another time. Nonetheless, groups intent of site destruction understand the potency of their actions and in order to combat this, historians and communities need to form flexible and effective strategies.

The answer, it seems, lies largely in education. Not just at universities, but between all groups involved in conservation and preservation. The unifying connection between local, global and cultural identities should not be underestimated in this instance and the focus should not be on who has the correct interpretation of these sites, but how we can preserve them for everyone’s interpretations. Groups such as Daesh already comprehend the impact the destruction of these sites has on a local and global scale with some videos showing the destruction of UNESCO sites, having been proven to be orchestrated. Real-time lidar and aerial photography shows instead, the looting and selling of antiquities to fund militias groups. This makes a stark statement about how more shocking to the world is the destruction of ancient monuments as opposed to the selling of ancient artefacts, but this is a blog for another time. Nonetheless, groups intent of site destruction understand the potency of their actions and in order to combat this, historians and communities need to form flexible and effective strategies.

At this event, local inhabitants, panellists and attendees aimed to define these issues and put forward how to address them. As part of this discussion, the film Destruction of Memory was screened. Based on Robert Bevan’s architectural book of the same name, the piece is a mixture of interviews, on-site footage, court-room hearings and interviews with the Director-General of UNESCO and the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, international experts and archaeologists. In short, the film covered issues including (but not limited to):

At this event, local inhabitants, panellists and attendees aimed to define these issues and put forward how to address them. As part of this discussion, the film Destruction of Memory was screened. Based on Robert Bevan’s architectural book of the same name, the piece is a mixture of interviews, on-site footage, court-room hearings and interviews with the Director-General of UNESCO and the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, international experts and archaeologists. In short, the film covered issues including (but not limited to):

- An explanation of what a war on culture means and the impact it has on contemporary societies.

- The challenges culture demolition causes for preservation and protection of material culture.

- A case study of Daesh and the organisation’s priority of cultural obliteration.

- The context of heritage loss within the wider scope of loss of life.

Perhaps unexpectedly, the film ended on a positive note, exploring the measures currently being pursued by multiple groups and specialists who are part of and work alongside local communities which protect, salvage and rebuild the history that has been lost. Augmented reality is allowing the rebuilding of sites, the funding of which allows for more educational frameworks to be put in place for future visitors and research. Knowledge of history, preservation techniques and wider contextual receptions of sites is being passed on to younger generations of historians, scientists, cultural leaders and archaeologists. Sites have been prioritised against future attacks and most importantly perhaps, these projects are providing cohesion between different cultures, whilst offering hope and visible regeneration of traumatised communities.

(Credit: Joseph Eid, 2014.)

(Credit: Joseph Eid, 2014.)

For me, this event finally settled the conflict in my own mind of juxtaposing the lost of heritage and the cost of human life in times of conflict. Cultural destruction is an organised endeavour which aims to wipe out all trace of a people in order to prevent its rekindling in the future. When the physical elements of a targetted culture can not be preserved, there are still ways to protect further attributes for future generations. This may come in many forms. It could be the remaining buildings, unique sculptures, every-day art, language, dialects or historical knowledge. What remains critical is the respect of local knowledge and requirements by external supporters. The culturally potent elements of heritage sites to the communities who live, cherish and protect them, may be different to the concepts of Daesh or European heritage, but they are just as critical for the survival of ancient history. The biography of an archaeological site or find does not stop the moment it is uncovered. Ancient culture and modern identities are intrinsically linked and as laws to protect cultural heritage are slowly developing, there must be greater education from unified communities about the importance and motivation behind artefact destruction (and indeed selling). Protecting ancient sites by working with local cultural identities will ensure even when columns fall, the greater community of world heritage will go on remembering them.

Resources:

The Destruction of Memory Film and Resources

When I moved to London in 1979, I ended up working in a hospital in Queen Square, which was just a ten minute walk away from the British Museum. I must have visited the museum hundreds of times over the years and the part I was always most drawn to – and still am – was the Assyrian section. I could spend hours trying to explain why, so all I’ll say here is that I thought there was something terrifying and at the same time beautiful about the massive winged bulls, the gates, the cuneiform writing and all the other artefacts. I love them more than I can describe in words, as if they’re some literally magical and enchanting remnant of another time and place. When I learned of these wonderful things being destroyed by savages and degenerates, I couldn’t bring myself to watch or read the news stories because I found them so distressing. I’ve read more than enough material over the years about the evil that men do to each other and to the creatures we share this planet with; it’s all awful, but the wanton destruction of antiquities – things that are Mankind’s shared heritage – is up there with the rest of the Devil’s work. Good on you for writing about all this, Bunny, because *I* certainly couldn’t.