Introduction to: The Aphrodite of Cyrene

Introduction

At the entrance of the Ure Museum, University of Reading, stands a freestanding statue depicting the ancient Greek goddess Aphrodite and her son Eros (Figure 1). The Aphrodite of Cyrene stands 1.07m tall (including the plinth) and is thought to date from the second century CE. The posture of this piece is a Roman adaptation of a famous original created by Greek sculptor Praxiteles, in the fourth century BCE . Localised replication of well-known sculptures made during, arguably, the height of Grecian art (500BC and 323BC) was widely practiced throughout Imperial Rome.

(Figure 1: The Aphrodite of Cyrene. Credit: Ure Museum)

Description

Examples of Roman (as opposed to Greek) manufacture can be seen, in part, due to the sculptures fragmentary condition. The holes seen in Aphrodite’s missing arms (visible in profile), reflect an infrastructure of metal rods that sit at the core of the marble facade, a stabilising process still practiced today. This joinery provided greater access to individual parts, enabling them to be carved and assembled separately. The iron rods also eased the removal of limbs and heads which occurred during cleaning, repainting or refashioning. Throughout the ancient world sculptures were often re-used and certainly throughout the Roman period, the heads of previous icons were often replaced with more contemporarily relevant portraits. The up-cycling of these stone vignettes ensured the iconography of Rome’s Empire adapted as frequently as its leadership changed .

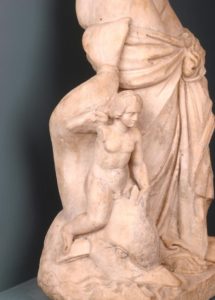

Further key elements of Roman manufacturing can be seen in the artistic form of the Aphrodite of Cyrene. Most early Greek sculptures were produced in bronze or limestone, sometimes worked around a central wooden form which would rot away, leaving a hollow centre . In contrast to these fairly lightweight sculptures, Roman statues were often carved in marble, creating much heavier artefacts. Plinths and counterweights were worked into Roman designs to provide the substantial support required to keep more marble-dominant pieces stable. The left profile of the Aphrodite of Cyrene provides an example of this, with the draped clothing along the back of the deity’s thigh acting as a support-plinth to her form, whilst the smaller Eros provides a counter balance on the right hand side (Figure 2). The addition of such distinctly Roman aspects prevents the piece from being an outright copy of the fourth century original, whilst the elements of freestanding casual stance and rounded anatomical features still adhere to the Classical style they desired to replicate.

(Figure 2: Close up of drapery and plinth. Credit: Ure Museum)

The Aphrodite of Cyrene in particular has a thematic approach to such additions, all of which reflect the symbolism of marine culture. These oceanic associations localised the identity of this statue, bridging the gap between Greek Classicism and Roman Provincial ideologies.

Context

The marine theme of the Aphrodite of Cyrene reflects the statue’s original context in Cyrene (modern day Libya in North Africa), where it was found in-situ, in a temple, during the Murdoch-Smith excavations in 1861 . Cyrene was a coastal colony throughout Greek and Roman dominance and played a comprehensive role in fishing trade. Ancient historian Herodotus recorded the high esteem with which Cyreneans held Aphrodite. Although the deity and her son, Eros are familiarly conduits of love and fertility, this sculpture focuses more specifically on the pair’s marine associations, highlighting the coastal context in which it was found. The site, thought to be a sanctuary to Aphrodite, was missing its key cult statue of Aphrodite Euploia; the seafaring aspects of the Goddess’ metaphorical repertoire . The Aphrodite of Cyrene clearly spotlights the goddess as the main paragon of the pair depicted by her much larger size, with Eros standing at approximately a quarter of her height (Figure 3). Although sometimes portrayed as a juvenile son, here, Eros’ size is hierarchical his form and expression being distinctly adult and proportionally more developed than a child. The quality and context of the Aphrodite of Cyrene, makes claims of her being the aforementioned missing cult statue, hard to dismiss.

The divine iconography of the ancient world was a culmination of personified desirable characteristics. Each deity accumulated, through origin allegories, a repertoire of attributes that acted as personalised and associable symbols. These could then in turn be used singularly or collaboratively as reminders of specific traits or fables. Aphrodite too, was given a moralistic back story, which ancient author Hesiod recounts in his Theogony. The story describes Aphrodite’s creation from sea foam, itself created as an excretion of the wounded genitals of Uranus, severed in betrayal by his son. The sea foam in the story can be seen carved into the plint of the piece, by Aphrodite’s feet (Figure 3).

(Figure 3: Close up of Eros. Credit: Ure Museum)

Further sea-connections can be seen in the low relief fish and the dolphin which Eros rides.

Sculptures were, then, exhibitions of Roman ideologies.The attributes of the Aphrodite of Cyrene are a good example of the entwinement of local cultural design (marina fish trade) and a deity’s national identification (Eros, origin story). The goddess’ other traits of love and fertility are still present. Nudity was uncommon in Roman sculpture of female (although male gods were almost always at least partially naked) but Aphrodite’s unclothed state is contextualised by the fabric gathered around the legs, implying she was initially clothed. Many readaptations of Praxitele’s original Knidos sculpture suggest elements of bathing, a notably accepted and expected Roman pastime, creating less promiscuousity and more demurity. The gathered cloth itself is not inconsequential. The garment is crumpled and deliberately ambiguous, perceivably being Greek or Roman in fashion, reaffirming the link between the two cultures and preventing contemporary fashions from aging the statue. The folds of the fabric are Classic, deeper than those of archaic relief friezes, but not as overtly luxurious as the wet look of later, High Classical forms . The garment(s) gather below the goddess’ slightly bent knees which suggest a possible perched or leaning pose. Similar adaptations sculpt Aphrodite with her arms aloft, wringing out her hair after bathing , but the fingers that remain on the front of the garment, suggest the missing arms on this piece were postured in a stance of redressing.

Conclusion

The accumulated additions of Aphrodite’s son Eros, the fish, dolphin and the sea foam to the previous fourth century BCE version, reflect the importance of legacy, prosperity and feminine modesty in second century CE Roman society. This statue is a good example of how successfully the Romans adapted renowned Greek forms to represent desirable Roman attributes. The Aphrodite of Cyrene statue reflects the importance of local acculturation to successfully convey Roman ideologies across a hugely diverse Empire. It is the multi-faceted propagandic values of such sculptures that ensured their long term survival in ancient art, acting as monumental reminders of local and national ideologies.

Ancient Editions:

Herodotus, Histories, 1998. Translated by R. Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bibliography:

Burnett Grossman, J. 2003. Looking at Greek and Roman sculpture in stone. California: Getty Museum Publications.

Casson, S. 1934. Techniques of Greek Sculpture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kristensen, T.M. & Stirling, L. 2016. The Afterlife of Greek and Roman Sculpture: Late Antique Responses and Practices. Beaverton: Ringgold Inc.

Neer, R. 2010. The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, A. & Harris, A. 2007. Recent Acquisitions and Conservation of Antiquities at the Ure Museum, University of Reading 2004-2008. Archaeological Reports, Volume: 54: 175-185.

Thorn. D. 2007. The Four Seasons of Cyrene. The excavations and explorations in 1861 of Lieutenants R. Murdoch Smith & Edwin A Porcher. In: Libyan Studies, volume 44: 5-11.