Comics, Contexts and Classics

Before the winter break, I attended a short seminar on the use of comics in the heritage sector. PhD student Katy Whitaker gave an interesting and informative introduction into the use of comics to educate, illustrate and emotively communicate historical messages.

Beyond the initial exploration of colour use and artistic styles, Whitaker drew on the work of fellow colleagues: Prima Anugerahanti, Louise Arnal, Nerea Ferrando Gorge who all had approached the use of art as not only a means of expression but as part of the academic process of understanding and breaking down their own research projects.

All the researchers’ presentations made it clear that each of them had initially approached the concept of using art differently. Some had deliberately used it as experimental archaeology, others had come across it by chance but all agreed that the scope for the integrated use of artistic expression during research projects became invaluable in surprising ways. That is not to say that they suggested painting a Dali-esk expression of time would help them analyse the role of time in quantum theory (….or would it?) but rather the process of breaking down and rebuilding key aspects of an argument was a visually creative parallel to say, the drafting a paper. Those with a staunchly scientific focus, for example, spoke of finding more accessible ways to portray sophisticated data, whilst theorists’ found breaking down their theory into a four-panel comic strip had helped to focus their core argument, without demeaning its complexities.

After the showcase, there was an open discussion in which some interesting comments came up regarding concerns of time management, the pros and cons of working with artists’ with different motivations, historical accuracy and the combined used of politicised messages in visual education tools. Although it was determined that there are some issues with the use of artistic expression within heritage education, there was an overall consensus that the use of such expression as part of the methodology of research is as advantageous as it’s outreach potential and needs further exploration.

For myself, as a creative person (whatever that means), I think there is an element of underestimated truth in this. The practicality of trial and error and the expressive nature required to emotively depict, for example, historic wars without (deliberate) political alignment or the ability to promote complex theories to new audiences is one that I believe could be invaluable to education. I do not have enough space on Facebook to truly do this talk justice, but I would like those of you that have a moment to consider what creative pursuits you enjoy and how could you use them to express a (work) subject that interests you. Could the challenge of combining the two help you to understand the subject matter further? What keystones would you use to explore and express your theories? If propagandised images, truths and ideals can be falsified or exaggerated to promote the ideology of motivated politicians, if pictures used in children’s books are to inspire and teach and fantastical films that cost millions are created for entertainment, why not use the same media which has already proved so potent, to aid and express the research questions of academics which are rooted in both passion and education? It is perhaps not the artistic ability that holds the most merit, but rather the style that not only successfully conveys a message, but helped to compose it. An idealist thought perhaps. But one I strongly suggest needs some consideration.

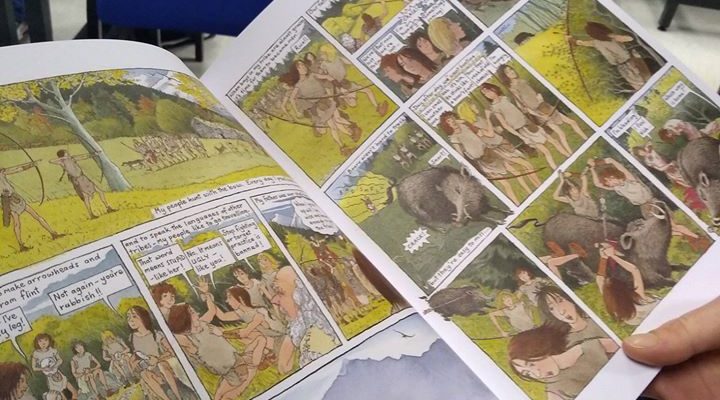

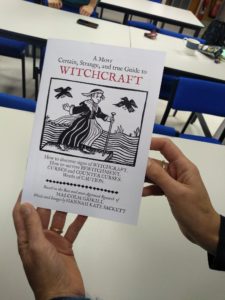

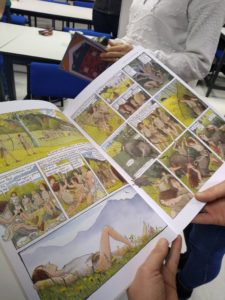

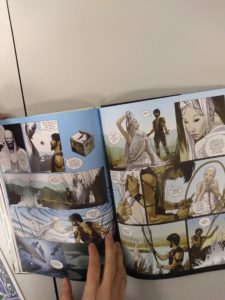

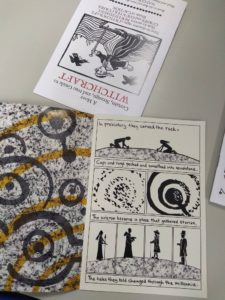

The images are of some of the examples Whitaker brought along for the attendees to look at. The variety of styles will no doubt appeal to a variety of audiences, but the key-value remains the same. Each tries to express a key concept, without disregarding its wider context. To see a good example seek out Joe Sacco’s “The Great War” as a mournful but important perspective of trench warfare.